Music by Monteverdi, Haydn and Schoenberg

Gotham Chamber Opera in collaboration with Armitage Gone! Dance Company (2008)

- Conductor Neal Goren

- Production Karole Armitage

- Scenic Design Vera Lutter

- Costume Design Peter Speliopoulos

- Lighting Design Clifton Taylor

- Make-up and Hair Design Hagen Linss

Cast:

- Ariadne; Emily Langford Johnson (dance) and Brenda Patterson (vocal)

Press:

The New York Times

Gia Kourlas

In Greek mythology, as in life, few situations are more excruciating than being dumped and not knowing why. The newest production by Gotham Chamber Opera, being performed at the Abrons Arts Center, brings just such a distraught heroine to the surface in Ariadne Unhinged.

The mezzo-soprano Emily Langford Johnson stars as Ariadne, the Cretan princess abandoned by her lover, Theseus. Stranded on the island of Naxos, she has only her thoughts to comfort her, and they are of little solace.

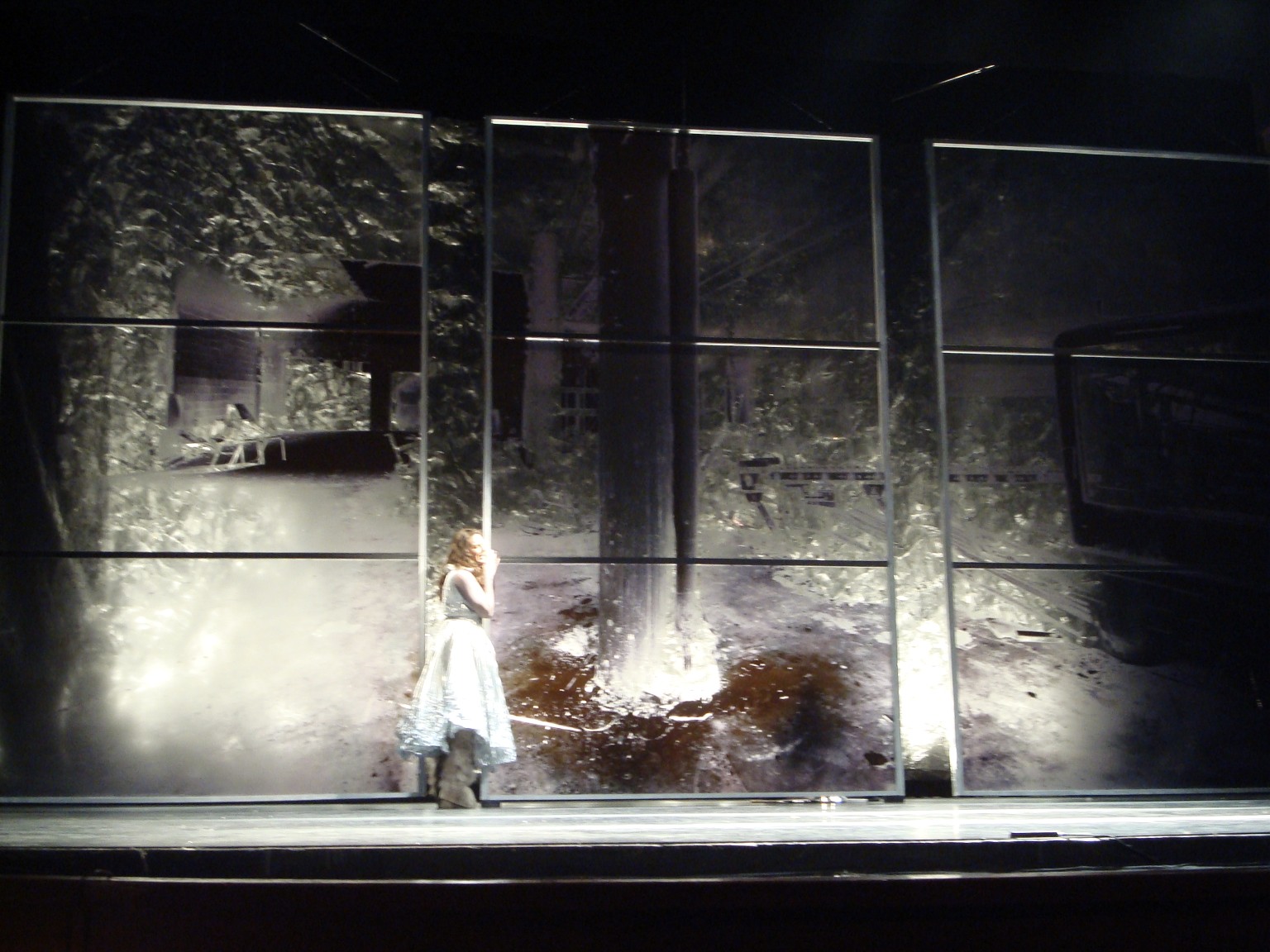

Ariadne Unhinged, a collaboration between the choreographer Karole Armitage and the conductor Neal Goren, who is the company’s artistic director, transports Ariadne to a place where madness engulfs her, yet she never descends into hair-pulling hysteria. Vera Lutter’s exceptional set, with three movable panes resembling glass negatives, provides a shimmering window into Ariadne’s hallucinations.

The production weaves together Monteverdi’s Lamento d’Arianna, featuring a performance on the theorbo by Daniel Swenberg; Haydn’s solo cantata Arianna a Naxos, with piano accompaniment; and Schoenberg’s strange and surreal Pierrot Lunaire. Music is arranged in collage form, allowing Ms. Johnson to move restlessly through Ariadne’s torments — her piercing sorrow in the slow, painful Monteverdi (“Let me die!”), her bittersweet flashbacks during the Haydn and her anguish, exposed and raw, in Pierrot Lunaire.

Throughout the ever-shifting terrain Ms. Armitage puts Ms. Johnson through her paces. Wearing furry boots and a voluminous, pleated dress by the costume designer Peter Speliopoulos that crinkles and shimmers like foil, she performs a beautiful mirrored duet with Frances Chiaverini, who appears, in a gleaming silver leotard, as her double. When Theseus, played by a bare-chested, handsome Ryan Kelly, appears in a vision, she slaps him silly.

Despite a few clunky moments when Ms. Armitage’s dancers introduce props that correspond to lyrics in Pierrot Lunaire — giant knitting needles, or a moon on a stick — the choreography remains pure. Ms. Armitage emphasizes line throughout, incorporating attitude turns and pristine arabesques that show, as when Ms. Chiaverini lowers to a lunge and lifts her arm with a slow, sure sweep, how seemingly rigid positions can melt and mold shapes (and emotions) like the voice.

The set, the costumes and Clifton Taylor’s lighting work together to give this production a tantalizing, metallic sheen. But just as alluring is Ms. Armitage’s direction. She has found a way to show cold-blooded despair with tenderness.

ConcertoNet

Harry Rolnick

Perhaps only the Gotham Chamber Opera would have the audacity to roam through the mind of Ariadne, who had been abandoned by her lover on the , the isolated Aegean island After 3,000 years, when neither Homer nor Bullfinch cared very much what she did with her time, some of New York's more spectacular talents have put together music, ballet and a strange shining setting to conceive a picture of Ariadne's mind.

Abandoning more conservative fare last night, this writer was attracted by venue, on this ancient immigrant section of New York, by the title, Ariadne Unhinged, by the melange of composers and of course by choreographer Karole Armitage. I had been told about her choreography by the otherwise serious historian Stella Dong. She had recommended Passing Strange on Broadway. The movements, counterpoint and split-second theatrics of that rock musical were so sharp that when Ms. Armitage's name appeared in the credits, it was time to visit ancient Grand Street and its old but very usable theater.

While called an opera, the work defies definition. Certainly it can be labeled a monodrama, since only one person sings for over an hour. Yet we are not interested so much in Ariadne as her mind, for the characters in her mind come alive on stage to torment her. In that sense, Ariadne Unhinged resembles a grotesque Elizabethan masque. Yet a masque had original music, and this...this composition had music from other sources. In that sense, the piece is a pasticcio, like Handel's Jupiter in Argos presented last week by Collegiate Chorale.

But most pastiche operas have music by a single composer, or, like Beggar's Opera, music of the same period. Here, Neal Goren took music from three different centuries of music, with Monteverdi, Haydn and Schoenberg. The results were most surprising.

Perhaps we should simply call it a "concept", the antithesis of Strauss's bubbly opera Ariadne auf Naxos. It starts with Ariadne alone on the stage, singing Monteverdi familiar Lamento d'Arianna. But she is not alone at all. The images summoned up by her mania begin to make their appearance around the strange background. They are sexless, androgynous, with skin-tight clothing. These spirits - peris? astral bodies? gnomes? Sylphs? - sometimes torment Ariadne with strange objects. More frequently they dance with her with figures close to classical ballet, but even closer to the naiads of Ravel's Daphnis and Chloe. One scene is of near copulation, another (with the single sex figure, of Dyonisus) is warded off her. But she still keeps singing.

Singing and dancing and playing harshly with these creatures of her manic imagination until the return of Monteverdi, and an uncomfortable of being alone, always alone on Naxos.

Emily Langford Johnson danced her way through the work when necessary, Sometimes reflecting the others, sometimes painfully against them. But simultaneously she had to sing, and her mezzo-soprano voice was not only full and rich, but - most important - dramatic no matter what the music. And that type of music was the core of the concept.

In theory, these musics of the Late Renaissance, Baroque and Expressionist should never have worked. Yet they did work in a most startling way. Monteverdi was used at beginning and ending reprise and one lament in the middle. Most of the agony was quite rightly placed in various out-of-chronology poems from Schoenberg's Pierrot Lunaire. At another point, the music changes entirely to Haydn's rare concert piece with piano, Arianna a Naxos.

Was the music supposed to send sudden fluctuations or startle the audience? That was not the result. The wonder came that the styles blended in so well together. And yes, they were to portray hysteria, but by switching from the classic to the expressionistic, one didn't feel the break so much as a fluidity of expression.

Perhaps in the concert hall, applause for one work creates a wall so that the next piece is completely different. Here, the sounds of theorbo, grand piano, and the multifarious sounds of the Schoenberg played into one another.

Not that those who abominate Schoenberg are going to get a thrill out of Ariadne Unhinged. But so much style has gone into the aluminum-style sets - sometimes reflective, sometimes transparent - so much expertise is in the dancing, and such a maximum of emotion comes out of the subtle changes of lighting, that this operatic concept has become a vital, original, and most of all, disturbing study of solitude and hysteria.

Financial Times

Martin Bernheimer

Neal Goren attempted something bizarre and dangerous at the intimate Abrons Arts Center on Wednesday. Ever inquisitive and ever resourceful, the conductor-impresario fused three musical disparities - none of them a bona fide opera - and gave the messy melange a clever catch-all title: Ariadne Unhinged.

The point of departure was Lamento d'Arianna, the surviving fragment of a long-lost opus that Monteverdi created in 1609. This gave way to the jolting expressionism of Schoenberg's Pierrot Lunaire, a series of genuinely looney tunes written in 1912. Although the macabre texts have nothing to do with our forsaken mythological heroine on Naxos, their moonstruck madness supports the Unhinged label. Relative sanity returned with Haydn's mellifluous cantata, Arianna a Naxos, written in 1789. Intentionally compounding the disorientation, Goren chopped each offering into little pieces, then shuffled the segments back and forth. Coherence be damned.

Karole Armitage, Goren's directorial accomplice, concocted modern-dance patterns and stage images more notable for theatricality than for choreographic inspiration. While Emily Langford Johnson, the virtuosic mezzo-soprano on duty, lurched, staggered, crouched and struck brave terpsichorean poses, Armitage's dancers, mostly unitarded, added passing decoration and distraction. They flourished naive props, dabbled in mild mime, formed human frames for the distraught diva in various combinations and permutations. At one point they mustered a pas de deux redolent of old-fashioned barefoot ballet. Initially the fussy manoeuvres looked intriguing in front of Vera Lutter's icy abstract photograph set. Eventually they seemed superfluous.

Still there was much to admire. Clad in a crinkly silver-debris gown over furry legs and hoofs (ask not why), the marathon protagonist moved with astonishing ease, physically and vocally, from Monteverdi's expressive lyricism to Schoenberg's dissonant Sprechgesang to Haydn's poignant drama. Daniel Swenberg provided stylish accompaniment on the theorbo for the Monteverdi. Goren sustained clarity and point with a spiffy chamber ensemble in the Schoenberg. Often Ariadne Unhinged was weird and wonderful. Sometimes it was just weird. Even then it was interesting.

Opera News

Joanne Sydney Lessner

Gotham Chamber Opera's Ariadne Unhinged,a collaboration with choreographer Karole Armitage, took the recital conceit of juxtaposing settings of identical text by different composers and expanded it into a full-length choreographed monodrama. Here, the story, rather than precise text, was the common thread: Ariadne, Princess of Crete, finds herself abandoned on the island of Naxos by her faithless lover, Theseus.

On May 7, mezzo-soprano Emily Langford Johnson sang Ariadne (Brenda Patterson performed on alternate nights), while her feverish imaginings were given life by Armitage's troupe of limber, expressive dancers. For an hour and ten minutes, Johnson vaulted from Monterverdi's Lamento di Arianna to Haydn's solo cantata Arianna a Naxos to Schonberg's Pierrot Lunaire and back again, ultimately completing each piece in its entirety. Though the Schonberg has no overt connection to the Ariadne tale, its fantastic imagery and tonal anarchy provided a useful medium to depict the heroine's descent into sadness. (Perhaps it was suggested by the commedia dell'arte subplot in Strauss's Ariadne auf Naxos, unused here.)

Looking like a prior-day Carrie Bradshaw in a flouncy, strapless metallic dress and wedge-heeled Wookie boots, Johnson was a committed, musically secure Ariadne. She gave herself fully to the concept and direction, gesturing gracefully through the reflective moving panels of the coolly elegant set, and shifting with little apparent effort from one musical style to the next. She was at her most confident and authoritative in the Schonberg (despite some patchy German), and though her voice was a bit steely in the Monteverdi, she displayed a luminous ring in the Haydn. It was a tall order, but Johnson gamely tackled every demand and acquitted herself beautifully.

In her notes, Armitage observed that the challenge was "to make the music and psychology of different eras come together as a cohesive whole." Yet paradoxically, for all the contrast inherent in the music, the evening suffered from a sense of sameness. This was due in part to a lack of variation within each composer's work, and a certain emotional artificiality. The two Haydn arias were the exception, offering Ariadne an escape from the island into a remembered past and a fantasy future. In "Dove sei, mio bel tesoro," Johnson sang longingly and sincerely, as her doppelganger danced a pas de deux with Theseus. Then, in the bravura "Ah! Che morir vorrei," Johnson physically attacked Theseus - a deliciously shocking choreographic turn that also freed her up for some of her best singing.